Place: Calvert Marine Museum

Location:

14200 Solomons Island Road

Solomons, MD 20688

Phone number: (410) 326-2042

Website: http://www.calvertmarinemuseum.com

Calvert Marine Museum

The Calvert Marine Museum has an assortment of exhibits on permanent on display. It is a fascinating museum at any time.

- The Drum Point Lighthouse was move from the Chesapeake Bay to the museum grounds. It is a very good example of a screw pile lighthouse.

- The museum is home to a small aquarium with a number of aquatic animals.

- There is a barn full of antique boats.

- The museum features an extensive display of fossils. (The proximity to the Calvert Cliffs, with their wealth of Miocene fossils, provide an abundant hunting ground for fossils.)

Coprolites

If I had included everything that I learned at the Universal Coprolite Day on the field trip post, the post would have been much too long. I have included more of the facts that I learned here for those who are particularly interested.

- There are two main kinds of fossils. Body fossils are preserved parts of the actual body of the prehistoric animal, such as teeth, bones, and shells. Trace fossils are impressions or marks left by an animal and then preserved, such as footprints, teeth marks, and shell impressions.

- Coprolites are fossilized poop left by an animal. Since the poop is not part of the actual body of the animal, it is considered a trace fossil. (Fossilized human poop is called paleofeces.)

- The word coprolite comes from Greek. Kaopros means dung, or poop. Lithos means stone.

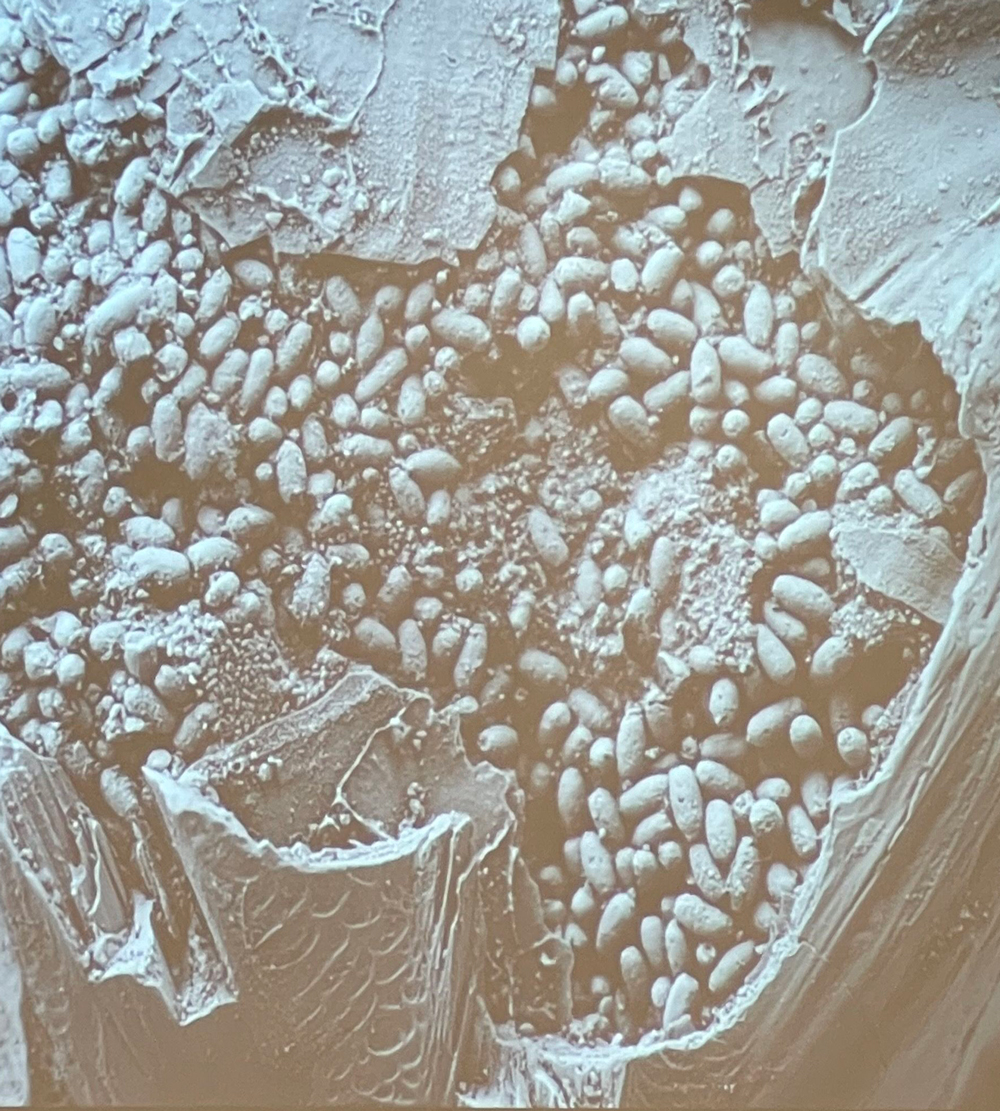

- Like other fossils, the original composition of the poop is replaced by minerals, such as silicates and calcium carbonates.

- Poop left by carnivores, who eat animals with bones, has a strong calcium carbonate composition when it leaves the body. The poop is on its way to becoming a fossil before the fossilization even starts. For this reason, most coprolites are from carnivores.

- It is very rare to find coprolite from an herbivore. The herbivore’s poop does not have a calcium carbonate composition. It is also more nutritious and usually is eaten before it has a chance to fossilize.

- From an early age, Mary Anning searched for fossils on the beaches of Dorset County in England. In the early 1800’s, Mary realized that the stones she found inside the abdominal area of skeletons must be fossilized feces, or poop. When she broke open the stones, she often found bones inside. Mary told a geologist friend, William Buckland, about her idea. He agreed with her and named the stones coprolites.

- Paleontologists often can learn from the coprolite composition what was eaten and whether the eater was a carnivore or herbivore.

- The actual identity of the animal that pooped is more difficult. Paleontologists often compare the shape and composition of the coprolite to the shape and composition of poop of currently living animals. For example, some coprolites have a spiral shape similar to the poop forming the the spiral intestines of present-day sharks. so they assume that the spiral coproplite is from a prehistoric shark.

- The location in which the coprolite is found also helps the paleontologist identify the animal. For example, the small pellet like coprolites found in the fossil of a prehistoric fish skull indicate poop from worms. These worms were eating the fish’s brain before the fish was fossilized.

Sources:

- Calvert Marine Museum paleontologists and volunteers at the Universal Coprolite Day.

- “Coprolite”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coprolite.

- Godfrey, Stephen and George Fransdsen. “Vertebrate-Bitten Coprolite from South Carolina.” The Ecphora, March 2016. http://calvertmarinemuseum.com/204/The-Ecphora-Newsletter.